When a master shares expertise on the particular trade you’re attempting to ply, you pay close attention. When the transfer of knowledge is done creatively, without pretention, you do so with pleasure.

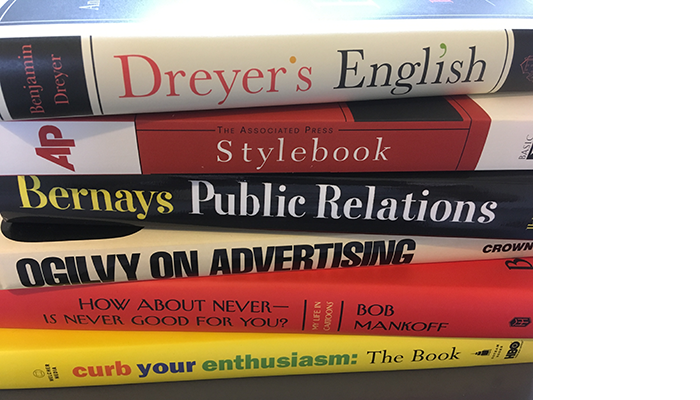

Which is why aspiring writers are in for a treat from Benjamin Dreyer, executive managing editor and copy chief at Random House and a great writer in his own right. His new book, Dreyer’s English: An Utterly Correct Guide to Clarity and Style, deserves its place alongside the communication classics: The Associated Press Stylebook, Ogilvy on Advertising, Public Relations by Edward L. Bernays, Adventures in the Screen Trade by William Goldman, How About Never — Is Never Good for You? by Bob Mankoff, and Curb Your Enthusiasm: The Book.

Dreyer simplifies difficult standards and sharpens (potentially) dull points by appropriate amounts of context, examples and levity. “Certain prose rules are essentially inarguable — that a sentence’s subject and verb should agree in number … Why? … simply because, I swear to you, a well-constructed sentence sounds better. Literally sounds better. One of the best ways to determine whether your prose is well constructed is to read it aloud.”

With obvious delight, Dreyer takes exception to a number of old-school grammatical rules and nonrules. “So far as I’m concerned, because they’re largely unhelpful, pointlessly constricting, feckless, and useless. Also because they’re generally of dubious origin …” Never starting a sentence with “And,” is one of a number of examples. “No, do begin a sentence with “And or “But,” if it strikes your fancy to do so,” Dreyer writes. But be selective, “Take a good look, and give it a good think.”

About the origin of the English language in its entirety, Dreyer expresses dismay. “It developed without codification, sucking up new constructions and vocabulary every time some foreigner set foot on the British Isles — to say nothing of the mischief we Americans have wreaked on it these last few centuries — and it continues to evolve anarchically.”

Dreyer also delivers plenty of quotable lines along the way. He suggests, “… which is a bit belt-and-suspenders, don’t you think?” about the redundancy of placing a comma before an ampersand (i.e. Eats, Shoots, & Leaves).

“The Trimmables” is another entertaining and educational chapter. “There’s a lot of deleting in copyediting,” Dreyer notes, “… we all encase our prose like so much Bubble Wrap … of restatements of information.” Examples of his dietary restrictions on prose (The bits in italics are disposable) include absolutely certain, cameo appearance, moment in time, plan ahead, and his favorite: “He implied without quite saying.”

As a cover-to-cover read, Dreyer’s English is remarkably entertaining. As a desktop reference, it is absolutely essential. And (or is it But) most of all, for the humble writer trying to gain confidence at his or her craft, Dreyer’s thorough and thoughtful guidance is inspiring.

(Apologies to Mr. Dreyer for the countless edits this and other Humble Sky essays undoubtedly deserve.)

I love the idea of reading your work aloud. This is something I will pass on to my students.