When time and space and comprehension slow us down, our natural inclination is to take shortcuts to streamline things. Not only with the limitations of everyday life, but with existential matters too. In fact, for centuries we’ve created and relied upon imagery, symbolism, allegories and similar tools as shortcuts to help us grasp some of humankind’s most profound mysteries.

Two distinct but intersecting incomprehensibles — one based on spiritual belief, the other on scientific theory — challenge the efficacy of this simplified form of “enlightenment.”

COSMIC BELIEF?

Most religions feature a prophet or chosen messenger, along with some form of sacred writings, to inform their beliefs . Without casting pretentious aspersions, there is reasoned debate whether these fundamentals are simply convenient shortcuts to accepting something too incomprehensible — some sort of unknowable higher power or energy or order of things.

“All my big thoughts have been coalesced into this,” Richard Rohr, the popular Franciscan friar and author, wrote in The Universal Christ. He explained the book’s theme in a recent profile “Richard Rohr Reorders the Universe” by Eliza Griswold in The New Yorker (2-2-20): “Jesus is an incarnation of that spirit [God’s love of the world], and following him is our ‘best shortcut’ to accessing it.” Rohr refers to this spirit as the “Cosmic Christ” and denounces the notion of Jesus as a “god-king,” which he explained “was pushed by political rulers, who used it to justify their own power, but it limited our understanding of divinity.”

Comedian Sarah Silverman put a less magnanimous, sharper point on religious doctrine: “It seems pretty clear to me that it’s a coping mechanism for people who cannot handle the not knowing of things.” In her interview for Judd Apatow’s book Sick in the Head: Conversations About Life and Comedy, the admitted nonbeliever said, “I am okay knowing I will never be able to comprehend the world.”

COSMIC THEORY?

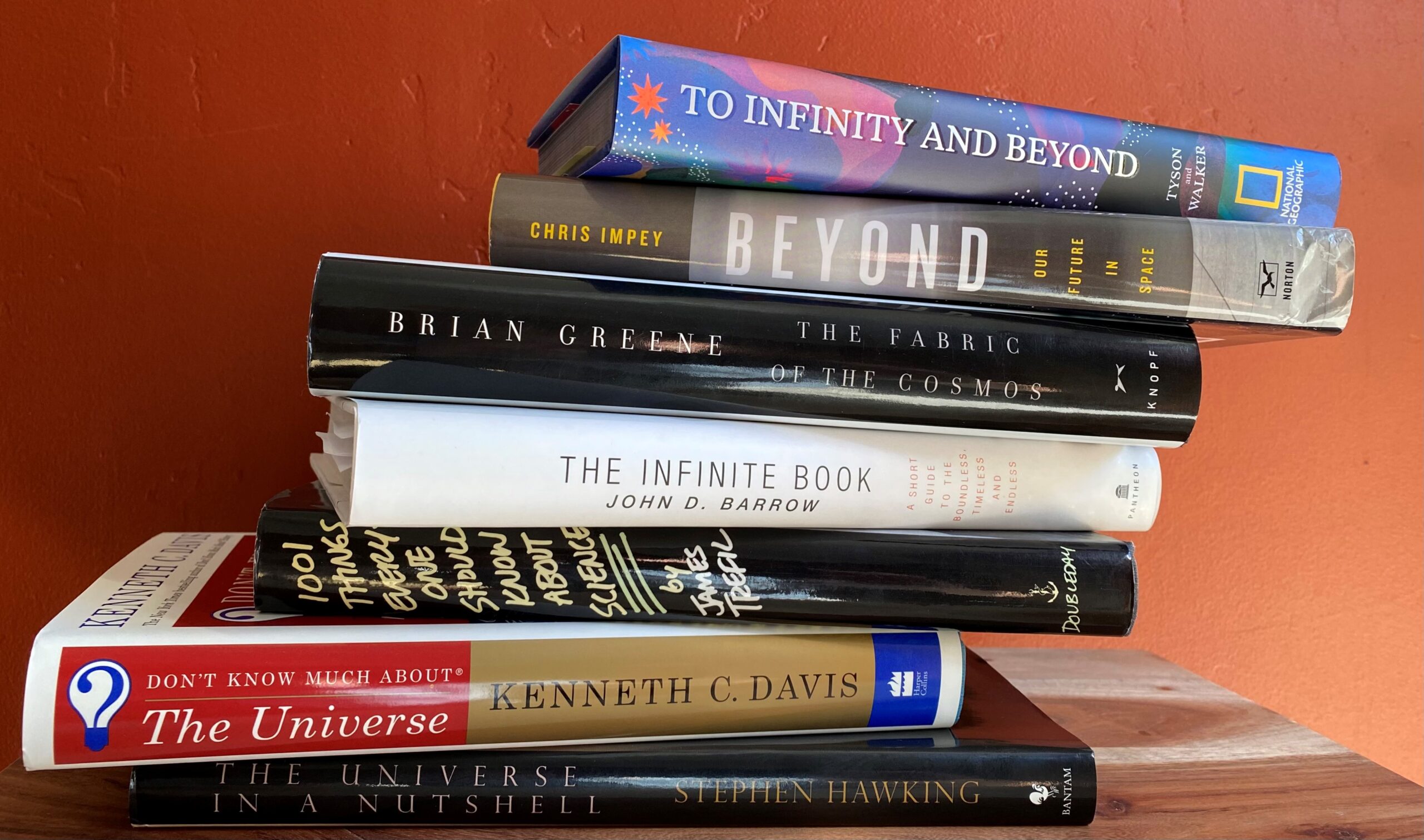

The other cosmic shortcut to which we blithely ascribe, is cloaked in science — and referred to as a theory, although it is essentially a belief. Infinity, the essence of the theory of an ever-expanding, inflationary universe, attempts to inform the incomprehensibility of questions like: “How far does outer space go; does it go on forever; does it have an edge?”

“Infinity characterizes an unending universe,” Cambridge math professor John D. Barrow explained in a recent essay for the university journal. “[Y]ou can never reach the end of all numbers by listing them, or the end of an unending universe by travelling in a spaceship.” The idea is to make people comfortable with the cosmic infinity, because … the alternative is certainly incomprehensible. As Barrow noted, “the idea of a finite universe immediately raises the question of what is beyond.”

In The Infinite Book, Barrow identified another reason why we may question the infinite. “One might have thought that a constant tension in the quest to grasp the infinite by human thought would have been the suspicion that the place of God was being usurped by anyone claiming to comprehend the infinite.” And then going still further down this rabbit hole, Barrow elaborated that this may actually be less of a problem than a concern that “infinite might be something that even God could not comprehend.”

On this intersection of the provinces of science and religion, cosmologist Stephen Hawking submitted: “Religion was an early attempt to answer the questions we all ask: why are we here, where did we come from? Long ago, the answer was almost always the same: gods made everything,” he wrote in Brief Answers to the Big Questions. “Nowadays, science provides better and more consistent answers, but people will always cling to religion, because it gives comfort, and they do not trust or understand science.” As only Hawking can do, that explains our belief and reliance on shortcuts in a nutshell.

COSMIC HUMILITY.

“If we long for our planet to be important, there is something we can do about it,” Carl Sagan boldly challenged us in Cosmos. “We make our world significant by the courage of our questions and by the depth of our answers.” He then offered this paradox: “It is said that men may not be the dreams of the gods, but rather that the gods are the dreams of men.”

All things considered, and with due humility, is it not better to accept the unknowable for what it is than feel obliged to personify and label it? Rather than showing it genuine reverence, various shortcuts become simplistic euphemisms for “We don’t have a clue.” Which further begs the question, Isn’t it better to be thought a fool than make up things to prove it?

We should also have more faith in conceptual thinking. George Coyne, the renowned Vatican astronomer (who died this February), was asked in an interview with The Times Magazine, “How can you describe the universe as a vast empty ineptitude, largely uninhabited, and still believe in … [the centrality of man?” he interjected.] He responded with this longcut on the cosmic connection between religion and science, “To our own knowledge of ourselves, we are unique in creation because of our own reflexivity.”

If we can just put our ego in check, we could accept that we don’t know what we don’t know. Then we can begin the journey to circumnavigate cosmic beliefs and theories in our quest to discover real universal truths. To paraphrase friar Rohr, our own humility is the most spiritual and enlightening tool of all.

Truly magnificent, Stuart!